In the misty hills and lively pubs of Ireland, a distinct musical tradition thrives, carried on the breath of musicians and the intricate silver body of the tin whistle. More than just an instrument, the Irish tin whistle is a vessel of cultural expression, and its soul lies not merely in the notes played, but in the delicate, rapid, and profoundly expressive world of ornamentation that dances around them. This system of decorative notes, known as ornamentation, is the very language that gives Irish traditional music its characteristic lift, pulse, and emotional depth, transforming a simple melody into a story told without words.

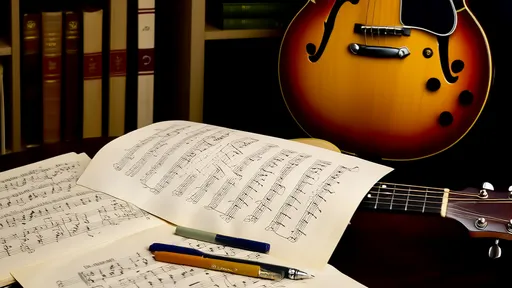

The foundation of Irish whistle playing is deceptively simple. The instrument itself, often called a penny whistle, is a six-holed woodwind instrument with a range of about two octaves. Its basic fingering is straightforward, easily mastered by a beginner in a matter of hours. Yet, to hear a master like Mary Bergin or Paddy Moloney play is to understand that technical mastery of the notes is merely the first step. The true artistry, the magic that makes the music sound authentically Irish, resides in the subtle and not-so-subtle decorations woven into the melodic line. These ornaments are not arbitrary flourishes; they are a grammatical system, a set of rules and conventions passed down through generations of musicians, primarily through the aural tradition. They provide rhythmic emphasis, articulate phrases, and add a layer of complex texture to what might otherwise be a plain tune.

Perhaps the most quintessential and frequently heard ornament in the tin whistle arsenal is the cut. A cut is a very short, grace note played above the main note, typically by quickly lifting and replacing a finger above the one currently sounding the primary pitch. For instance, if playing a sustained D note, a musician might flick their finger off the E hole for a split second, creating a fleeting high E sound before the D continues. The purpose of the cut is not to draw attention to itself as a separate note, but rather to punctuate and accentuate the main note, giving it a sharper attack and a percussive quality that enhances the rhythm. It acts as a musical dagger, sharply defining the pulse of a reel or jig.

In direct contrast to the sharp interruption of a cut, the strike or tip is a grace note played below the main note. Executed by quickly tapping a finger on a hole below the primary note, the strike provides a softer, more subtle emphasis. Where a cut might be used on a strong downbeat, a strike often ornaments a weaker beat or a note within a passing phrase, adding a gentle push or lift without the sharp attack. Think of the difference between a sharp tap and a soft brush; both provide texture, but of a decidedly different character. Musicians often use cuts and strikes in combination, creating a conversation of high and low accents within a single musical phrase.

Then there is the roll, a more complex ornament that is essentially a combination of a cut and a strike wrapped around a main note. A full roll effectively turns a single note into a sequence of five distinct sounds: the main note, a cut above, the main note again, a strike below, and a final return to the main note. This all happens in the space of one beat, creating a beautiful, trilling effect that is synonymous with Irish music. The roll requires precise finger control and timing to execute cleanly, ensuring the grace notes are fleeting and the rhythm remains tight and unwavering. It is a cornerstone ornament, used to add flourish and energy to longer notes, especially in the lively dance tunes.

Beyond these core ornaments lies the cran, a ornament particularly associated with the uilleann pipes but effectively adapted by advanced whistle players. A cran is a series of rapid cuts on a single note, producing a stuttering, rhythmic effect that is incredibly powerful for accenting a phrase. It is a more aggressive, rhythmic ornament than the melodic roll. Another vital technique is the slide, where a finger slides slowly to uncover a hole, bending the pitch up to the desired note rather than striking it directly. This creates a soulful, vocal-like quality, full of longing and emotion, that is especially effective in slow airs and laments.

It is crucial to understand that this system is not a rigid set of instructions to be applied mechanically. This is where the art separates itself from the science. The choice, placement, and density of ornaments are what define a musician's individual style. A tune played by two different master whistle players will be recognizably the same melody, but their personal storytelling will be articulated through their unique approach to ornamentation. One player might favour dense, rapid-fire rolls and cuts, creating a torrent of sound. Another might use a more sparse, thoughtful application, letting the melody breathe and using a well-placed slide for maximum emotional impact. The music is a language, and ornaments are the dialect, the accent, and the inflection with which each musician speaks it.

Learning this intricate system is a journey that has traditionally happened by ear. Apprenticeship, whether formal or informal, involved sitting next to a seasoned player, listening intently, and attempting to replicate not just the notes, but all those subtle graces and rhythmic pushes. Today, while sheet music and online tutorials can provide a roadmap, the true essence of stylistic ornamentation is still best absorbed through attentive listening. The nuance—the exact timing of a cut, the pressure of a slide—is nearly impossible to notate perfectly on paper. It is a feeling, a rhythmic instinct that must be absorbed from the living tradition.

The Irish tin whistle, therefore, is far more than a simple beginner's instrument. Its physical simplicity is a canvas for immense artistic complexity. The sophisticated system of ornamentation—the cuts, strikes, rolls, and slides—is the heart of its expressive power. It is this language of decoration that makes the music leap and cry, that makes it impossible to sit still during a jig and breaks your heart during a slow air. It is a testament to a culture that values storytelling, community, and the profound beauty that can be found in weaving intricate patterns around a strong, simple melody. To understand Irish music is to listen not just to the tune, but to the whispers, shouts, and sighs that happen in the spaces between the notes.

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025