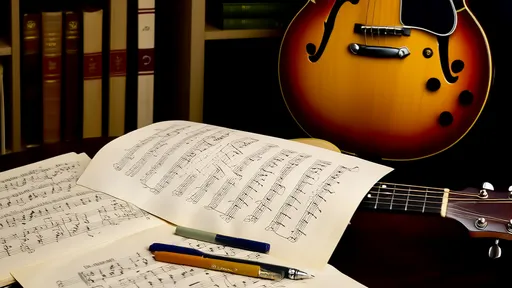

In the heart of Andalusia, where the raw emotions of flamenco echo through sun-drenched plazas and intimate tablaos, the guitar is more than an instrument—it is the lifeblood of the art form. While the impassioned vocals, percussive dance, and haunting melodies often capture the audience's immediate attention, it is the underlying rhythmic structure, known as compás, that gives flamenco its soul and unwavering pulse. To understand flamenco guitar is to immerse oneself in the complexities and traditions of compás, a system so intricate and vital that it defines the very essence of each palo, or style.

The term compás transcends the simple Western notion of a time signature or a metrical cycle. It is a profound concept encompassing the cyclical rhythm, the accent patterns, the emotional drive, and the cultural context that binds the musicians, singers, and dancers together. It is the unwritten law of timing and feel, a deep-seated knowledge that flamenco artists internalize from years of immersion. Without a solid compás, even the most technically proficient guitarist is merely playing notes; with it, they are telling a story, evoking duende—that mysterious state of heightened emotion and authenticity.

Flamenco is not a monolithic genre but a vast tree with many branches, each represented by a distinct palo. Every palo is characterized by its own unique compás, varying in cycle length, accent placement, tempo, and mood. The most fundamental and widely recognized compás is that of Soleá. Soleá is often considered the cornerstone of flamenco, a solemn and profound palo played in a 12-beat cycle. However, the counting is not a simple 1-2-3-4; it is grouped in a specific pattern of accents: 1 2 3 | 4 5 6 | 7 8 9 | 10 11 12, with strong accents typically falling on beats 3, 6, 8, 10, and 12. This creates a syncopated, rolling feel that is both majestic and deeply melancholic. The guitarist's rasgueado (strumming) patterns and llamada (call) phrases are all built around this architecture, providing the foundation for the singer's lament.

Closely related to Soleá is Bulerías, the quintessential fiesta palo often used to conclude a flamenco gathering. It shares the 12-beat cycle but is played at a much faster, exhilarating tempo, brimming with joy, mischief, and virtuosic energy. The accent pattern is even more syncopated and flexible, with a strong emphasis on beats 12, 1, 2, 3, 6, 8, and 10. Bulerías is the ultimate test of a guitarist's compás, requiring impeccable timing and the ability to interact spontaneously with dancers who might break the rhythm with sharp, sudden footwork (zapateado) or a dramatic turn. It is chaotic, alive, and utterly compelling.

In stark contrast to the 12-beat cycles stands the vibrant 4-beat compás of Tangos and Rumba. These palos are more direct, groove-oriented, and accessible, often serving as a gateway for newcomers to flamenco rhythm. The compás for Tangos is a sturdy, four-square pattern: 1 2 3 4, with accents on 2 and 4, though it is often phrased with a distinctive swing. The Rumba, with its infectious, danceable rhythm, has traveled the world and influenced popular music, but its core compás remains a driving, celebratory 4/4 beat that compels movement.

Then there are the palos in binary form, like Fandangos and Seguiriyas. Fandangos, in its many forms, often uses a 5-beat cycle (or a 3/4 or 6/8 feel depending on the regional style), offering a more lyrical and less rigidly cyclical structure. Seguiriyas, on the other hand, is one of the most serious and tragic palos. Its compás is a unique 12-beat cycle that is counted and felt differently from Soleá, often phrased as 1 2 | 3 4 5 | 6 7 | 8 9 | 10 11 12, with a heavy, dragging emphasis that mirrors the weight of its themes of death and despair. The guitarist must convey this profound sorrow through every stroke, making the compás feel almost like a funeral march.

For the flamenco guitarist, mastering compás is a lifelong pursuit that begins not with complex solos, but with the humble toque a compás—playing in time, providing the rhythmic foundation. This is the role of accompaniment (el acompañamiento). The guitarist must listen intently to the singer's phrasing (cante) and the dancer's footwork, responding to their cues with rhythmic calls (llamadas) and closing phrases (cierres) that signal transitions. The entire performance is a conversation held together by the mutual, unshakeable understanding of the compás. A guitarist might play a simple chord progression for bars on end, but the magic lies in how they articulate the rhythm through techniques like the sharp, percussive golpe (tapping the guitar's body) or the rapid strumming of rasgueado to build intensity.

The tools to articulate compás are found in the guitarist's right hand. The rasgueado is not merely a flurry of strumming; it is a precisely timed articulation of the rhythm. Different patterns—whether a four-finger abanico or a simpler three-stroke pattern—are chosen to highlight the accents of the compás. The picado (scale runs played with alternating fingers) and the arpeggio (plucking individual strings of a chord) are also executed with rhythmic precision, ensuring that every note, no matter how fast, lands squarely within the cycle. Even the left hand contributes with lligados (hammer-ons and pull-offs) that create fluid, rhythmic phrases without the need for a pick strike.

Ultimately, the true mastery of compás is not achieved in isolation with a metronome. It is forged in the juergas (informal flamenco parties) and peñas (flamenco clubs), where musicians, singers, and dancers gather in a communal celebration of the art. It is here that the guitarist learns to breathe with the compás, to feel its push and pull, and to understand that it is not a rigid cage but a flexible framework for expression. The compás might speed up (accelerando) in a moment of heightened passion or slow down (ritardando) for dramatic effect, but it never loses its core identity. This living, breathing practice is what separates academic knowledge from true flamenco artistry.

In conclusion, the compás rhythm patterns of flamenco guitar are the invisible architecture upon which this powerful art is built. They are the coded language of emotion, the map that guides every performance from the deepest sorrow of a Seguiriyas to the unrestrained joy of a Bulerías. To play flamenco guitar is to become a keeper of this rhythmic tradition, to honor its past while engaging in its vibrant, ever-evolving present. It is a demanding path, but one that offers the profound reward of speaking directly to the human soul through the universal language of rhythm.

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025