In the high-stakes world of live performance, the sudden failure of an in-ear monitor system can feel like a performer's worst nightmare unfolding in real time. These discreet devices, commonly known as ear monitors or IEMs, have become the technological backbone of modern concerts, providing artists with a personalized mix of music, backing tracks, and cues directly into their ears. They allow for precise auditory control on chaotic stages, protecting vocals from the roar of the crowd and the thunder of amplifiers. Yet, this reliance on technology introduces a critical vulnerability. When an ear monitor fails, it doesn't just create an inconvenience; it threatens to derail an entire performance, leaving an artist sonically stranded and disconnected from the very elements that guide their show.

The immediate sensation for a performer experiencing this failure is one of profound isolation. The custom-mixed world in their ears—a blend of their own voice, fellow musicians, click tracks, and pre-recorded elements—vanishes without warning. It is replaced by the muffled, booming cacophony of the live arena. This disorienting shift can trigger a surge of panic, a natural fight-or-flight response to a sudden loss of a primary sense during a demanding task. The instinct might be to stop, to signal for help, or to rip the useless device from their ear. However, the show, as the old adage goes, must go on. The first and most crucial step in any emergency protocol is not a technical fix, but a mental one. Performers are trained to acknowledge the panic without surrendering to it. A deep, deliberate breath becomes an anchor. The focus must instantly shift from the internal, missing audio world to the external, visual reality of the stage. This mental pivot is the foundation of all subsequent recovery actions.

With composure maintained, the artist must immediately establish a new connection to the music. This is where years of muscle memory and fundamental musicianship become their salvation. The click track, that essential digital metronome guiding the tempo, is now gone. The performer must now internalize the beat, relying on the physical vibrations of the bass drum through the stage floor or visually locking in with the drummer's movements. Eye contact with bandmates transforms from occasional reassurance to a critical lifeline. A quick nod, a gestured count-in, or a wide-eyed signal of distress can communicate the problem and coordinate the response without a single word. The monitor engineer, situated at the front-of-house mixing console, is typically the first line of technical defense. Performers often have a pre-arranged, unmistakable hand signal—like a finger pointed at the ear followed by a slashing motion across the throat—to alert the engineer to a complete monitor failure.

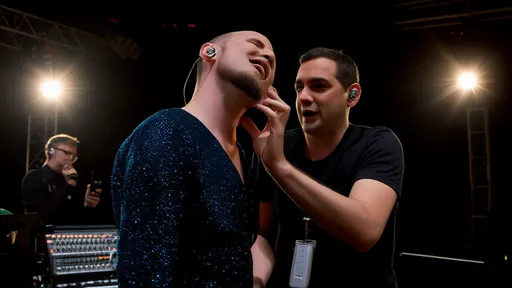

Simultaneously, the on-stage audio technician or guitar tech becomes a key physical ally. While the monitor engineer troubleshoots the signal from the console—checking transmitter packs, antennae, and frequency interference—the stage tech can spring into action. Many artists, especially lead vocalists, utilize a dual-system setup as a primary safeguard. This involves wearing two separate in-ear monitors, each connected to a different transmitter and receiver pack. It is a belt-and-braces approach; if one system fails, they can seamlessly switch to the backup by simply muting the dead ear and focusing on the live one. For those without a dual system, the stage tech's role is to perform a rapid physical checklist: ensuring the receiver pack is powered on, the volume is up, the cable is securely plugged into both the pack and the earpiece, and that the pack's antenna is properly positioned. In some cases, a simple battery replacement in the body-pack receiver can restore the signal in a matter of seconds.

When these immediate technical solutions prove futile, performers must fall back on a more primitive but reliable tool: the stage wedge monitor. Before the ubiquity of in-ear systems, these wedge-shaped speakers placed at the front of the stage were the sole means for artists to hear themselves. Most professional stages still keep a number of these wired and active, precisely for such emergencies. A performer can quickly move to a position where they are standing directly in front of a wedge. The monitor engineer, now aware of the problem, can swiftly route a rough mix of the most essential elements—lead vocals, snare drum, and bass—to that specific wedge. The sound quality will be a far cry from the pristine, isolated mix of the in-ears. It will be louder, feedback-prone, and a messy blend of the entire stage, but it provides enough auditory information to stay in time and in tune, serving as a crucial sonic life raft.

Perhaps the most challenging scenario is a failure that affects not just one, but the entire band's in-ear systems simultaneously. This could be caused by a major RF (radio frequency) interference event or a failure at the main transmitter. In these situations, the recovery becomes a collective effort of communication and adaptation. The band must revert to playing almost entirely by feel and sight, much like musicians did for decades before this technology existed. The drummer becomes the undisputed leader, setting a clear, solid, and visually obvious tempo. Guitarists and bassists will need to watch the drummer's hi-hat and kick drum movements intently. Vocalists must rely on the physical sensation of singing and the limited sound that travels through their own skull (bone conduction) to approximate pitch. The mix from the main PA system, blasting out towards the audience, will also wash back onto the stage, providing a distant, echo-laden guide.

Beyond the technical and physical adjustments lies the art of performance itself. A skilled performer knows how to mask a technical disaster from the audience. Instead of displaying frustration or fear, they channel the adrenaline into their performance. They might move closer to the other musicians for better visual cues, engage more directly with the audience to create a distraction, or simplify their parts to avoid complex passages that require precise auditory feedback. The audience is often completely unaware of the silent crisis unfolding on stage, perceiving only a passionate and engaged performance. This ability to project confidence and professionalism under extreme pressure is what separates seasoned veterans from novices.

Ultimately, a comprehensive emergency protocol for in-ear monitor failure is built on a multi-layered strategy. It begins with mental fortitude and rigorous pre-show preparation, including thorough soundchecks to identify potential RF issues and test backup systems. It relies on redundant technology, such as dual IEM systems and active stage wedges. It is executed through clear, non-verbal communication between the artists, the monitor engineer, and the stage crew. Finally, it is underpinned by raw, fundamental musicianship—the ability to play and sing from a place of feel and connection rather than technological dependency. By mastering this protocol, performers transform a potential catastrophe into a mere hiccup, ensuring that the music never stops, no matter what.

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025